Pat Ratkowski continues his investigation into the source of the detergent discharge into Sligo at Maple Ave. Things get interesting as he and DEP Environmental Specialist Alex Torrella go underground in the search.

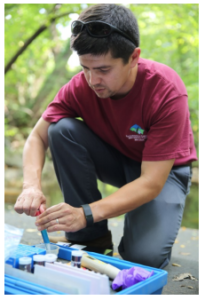

When we last checked in with DEP’s effort to find the source of chronic illicit detergent discharges at the Brashears Run storm water outfall pipes along Maple Avenue in Takoma Park, we were following DEP Environmental Specialist Alex Torrella on his dye test tour. As part of the search effort, he has poured fluorescent dye down apartment building laundry room sinks up and down Maple Avenue.

After he does so, he heads to the Brashears Run outfall to measure for detergent and chlorine, and to see if the dye shows up in the outflow during the next several hours.

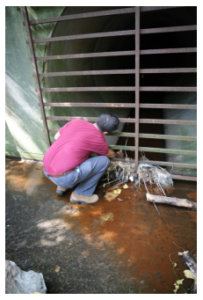

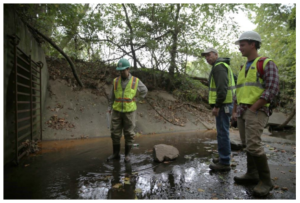

If it does, it means that the apartment building’s laundry room is improperly hooked up to the storm water system. If it doesn’t, it means that it is time for him to move on and test the next apartment building’s laundry room. After nine months and more than a dozen apartment buildings tested, Torrella was still no closer to finding the source(s) of the daily releases. So he and DEP Environmental Compliance Supervisor Steve Martin decided it was time to take the next logical step – underground, inside the storm water system. And so it was that I recently met up with Torrella and Greg Harless, Project Manager/ Senior Inspector with Stormwater Maintenance & Consulting, as they prepared to squeeze past the Brashears Run grate and head up the 72-inch wide storm water tunnels in search of errant suds.

The plan was to wait for one of the many illicit discharges at Brashears Run to begin…

and then track it underground through the storm water tunnel system, in real time, to its source. While there would occasionally be ladders leading to manhole covers at street level and junctions with other storm water pipes, we would be traveling between 5 and 10 feet underground, rapidly losing any ability to communicate with the outside world after the first few hundred feet of the pipe. Greg Harless would wear a multigas portable meter that would keep track of oxygen, combustibles, carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulfide levels in the air as we traveled through the storm water system. Perhaps the gravest potential dangers were the collapse of a portion of the pipes or the possibility of large, unexpected pulse of water from a torrential storm or massive water main break – both, thankfully, extremely unlikely. Nonetheless, preparing to leave sunshine and sky a kilometer behind for a hypogeal 6-foot concrete cylinder lit only by our flashlights briefly conjured up a variety of unhelpful images, ranging from Jean Valjean to The Descent. After waiting 30 minutes with no sign of suds, we decided to head into the pipe and hope that an illicit discharge would begin during our exploration so that we could trace it back to its source. The plan was to spend about an hour underground, documenting pipe junctions and manhole access points along the way, with Harless using a measuring wheel to track our distance from the Brashears Run outfall. Steve Martin would stay behind at the outfall grate to act as our confined space attendant in case of any trouble. Brushing aside memories of the cult classic C.H.U.D., I put on a hard hat and followed Harless and Torrella past the outfall’s cover grate and into a different world…

To Be Continued …